What Remains Part 1: Looking Back While Adrift

For nearly a decade, in the quiet solitude of my studio, I reconstructed the faces of those who walked this Earth millions of years before us. My hands, guided by statistical methodologies and anatomical understanding, traced the contours of skulls that once held minds perhaps not so different from our own. Each fragment of bone felt like an invitation—a clue in an ancient mystery that stretched across the vast expanse of evolutionary time. Who were these beings who shared our lineage but not our species? What stories might their reconstructed faces tell? And beneath these questions lay something more personal: a search for my own place in the grand cosmic narrative.

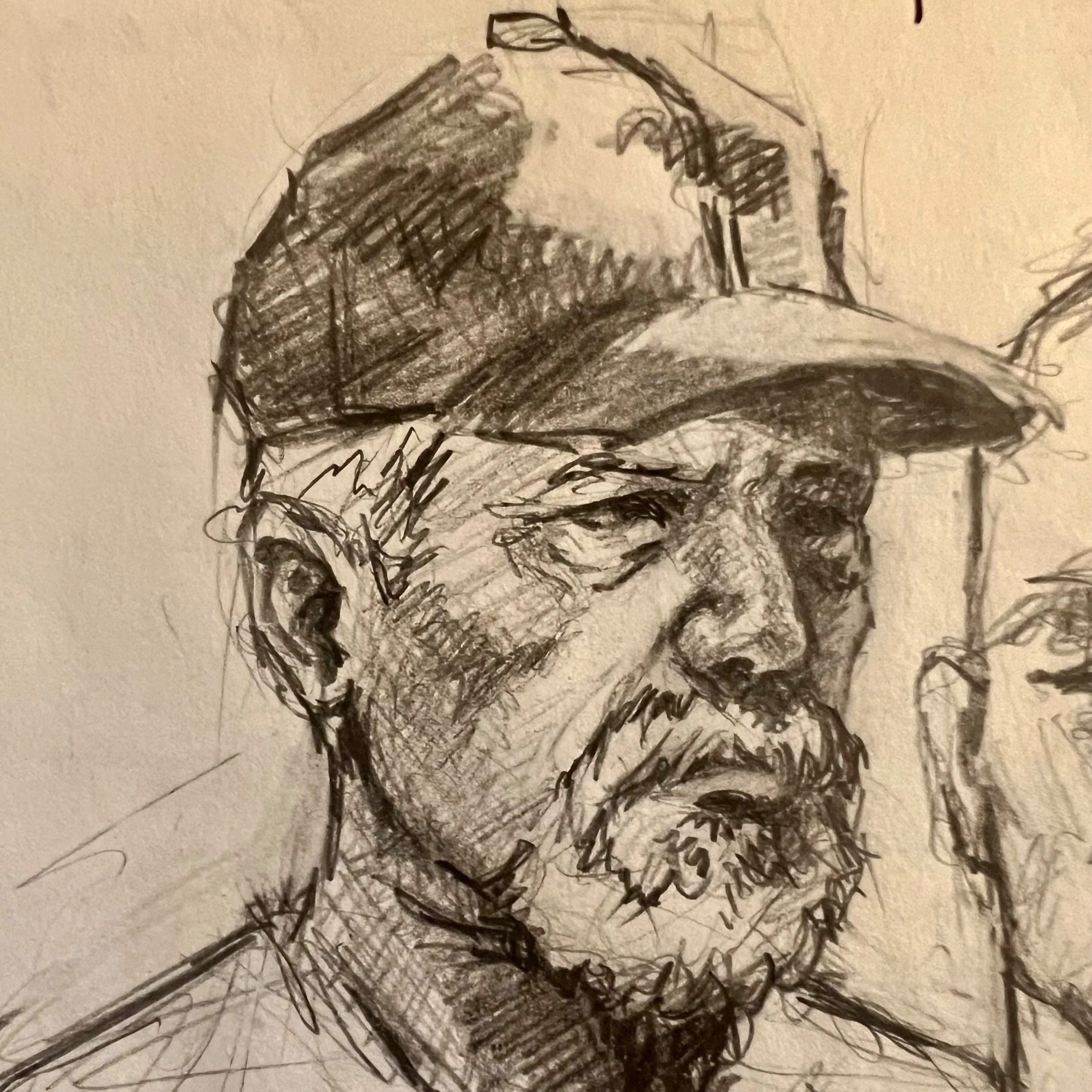

While my scientific reconstructions became my focus for nearly a decade, they were built upon a foundation of portraiture that had been with me since childhood. It's important to reflect that portraiture is an intimate practice with a history intertwined with class, hierarchy, and reverence. Be that as it may, for me it has always been a way to connect with those around me—by attending closely to the forms that conspire to create their faces. This practice began long before the scientific work. As a child, I would draw restlessly in an effort to understand the world around me: the mysteries written on the faces of family members and strangers alike. That drawing turned into sculpting in clay, always with a yearning curiosity—a desire to reach toward connection with the person before me. To, as it were, listen to the story they couldn't, wouldn't, or perhaps shouldn't tell me.

It's been said that people wear their lives on their faces. While I can't speak to the objective truth of that claim, I can say that every person I've sculpted has invited me to notice their particularities. The more I looked, the less "like others" each subject became. The less I could categorize them, and the more I could see their singular experience—their particular suffering, their fleeting time here. And in seeing that, I found myself less alone. More connected. The more I attended to the person before me as they were—rather than what I thought they should, could, or would be—the more stillness and belonging I found.

In those early years, after showing a subject their portrait, I was often met with tenderness. Especially when I was young, I didn't think much of it. I simply felt the warmth of their smile. Their satisfaction urged me to keep going. Only recently have I begun to understand that perhaps, in that short time, they felt seen. Appreciated. Honored.

As this practice continued, I became so focused on the forms of my subjects that I began to want to peer behind them—to understand the mechanisms and structures that make the human face. This curiosity led me—at least for a time—away from observation-based portraits and toward the anatomical structures we all share. That shift came with an unplanned but growing love for the scientific method, and with it, a sense of awe at the worldview it revealed. Learning that all primates share essentially the same muscular and skeletal structure filled me with wonder: how deeply connected we are, not just to each other, but to our fellow non-human animals as well.

This newfound appreciation for shared anatomy eventually led me to the fossilized remains of our distant anthropological antecedents—a collection of individuals who offered a rich and complex vision of what I began to think of as "non-human humanity." These beings lived in the beautiful grey area, beyond the neat boxes of race, nationality, creed, or even species. And so I began to sculpt them, too. Each a kind of frontier, not only in evolutionary terms but in my own search to understand what makes us human.

My sculptural work became, in a sense, a kind of translation—converting the raw data of bone into the language of face, transforming measurements into meaning. Each reconstruction was both a scientific endeavor and a deeply human one. I wasn't merely cataloging our evolutionary past; I was trying to look it in the eyes. To see in our ancestors' reconstructed faces something of ourselves—finite beings in an ancient lineage, sharing not just DNA but perhaps also the fundamental experience of consciousness itself: awareness of our own mortality.

As you might begin to see, dear reader, my practice was never solely artistic or scientific. It was a means of processing a deeply personal search for orientation and place in the world. Having stepped away from the structured beliefs of my vaguely evangelical, quasi-Afro-Cuban Christian upbringing, I found myself unmoored— set adrift in unknown existential waters. The answers I had been given growing up were beginning to fray—not just about morality or creation, but about what happens when it all ends. The promise of an afterlife, once so matter-of-fact, began to feel not merely uncertain, but unlikely in the face of mounting evidence about the natural world. The narratives that had once offered certainty dissolved entirely, leaving behind a quiet ache for coherence.

That unraveling reached its peak during my early college years, when I found myself far from home and exposed to a multitude of new ideas—ways of thinking I had never known existed. I wanted to understand my place in the world—but I no longer trusted the old answers. And without them, I found myself face-to-face with a question I hadn't realized was hiding at the center of everything I was doing: What, then, do I do with a life that ends? Not one that ends with an eventual reassembly of our “selves” in a nice place, no, dear reader, I mean one that ends. Full stop.

In that dark sea of existential dread, I found an unlikely port of respite: the scientific worldview. As a child, I was bored by science—taught it poorly, perhaps, or simply too inattentive to grasp its beauty. But now, in the wake of unraveling faith, I was drawn to the wonder-filled humility and clarity of thinkers like Carl Sagan and Richard Dawkins. They spoke of the natural world with reverence and rigor, and it felt like a revelation of sorts. "There is grandeur in this view of life," Darwin had written—and they echoed that grandeur without dogma. Where once I had been offered confident, yet ambiguous answers by adults and figures of authority, I now found something far more liberating: a worldview in which "I don't know" was not a failure, but sometimes the most honest—and celebrated—response.

But one of the most profound teachings from this time came from the first pages of Unweaving the Rainbow—a book on how the scientific worldview can reveal the poetry of reality and still stir an appetite for wonder. Dawkins opens with:

"We are going to die, and that makes us the lucky ones. Most people are never going to die because they are never going to be born. The potential people who could have been here in my place but who will in fact never see the light of day outnumber the sand grains of Arabia. Certainly those unborn ghosts include greater poets than Keats, greater scientists than Newton. We know this because the set of possible people allowed by our DNA so massively outnumbers the set of actual people. In the teeth of these stupefying odds it is you and I, in our ordinariness, that are here."

These words did much to dampen my growing existential anxieties and filled me with the inspiration to - as he later writes: "...understand why our eyes are open, and why they see what they do, in the short time before they close forever."

So I carried forward my lifelong impulse to record and connect with the stories written on the faces of those around me, now coupled with a growing fascination with our shared evolutionary past. I believed that by piecing together the faces of those who came before us, I might uncover something essential—something universal—about what it means to be human. At that time, it felt to me like a finite life well spent.

The studio became a kind of sanctuary where time collapsed. As I shaped clay over the brow bone of a Neanderthal or sculpted the nostrils of a Paranthropus, I felt an intimacy with these long-gone individuals. Through my hands, it felt possible to ask the same questions I once posed while drawing the woman across from me on the train. Who was this person? What did they love? What made them laugh, or grieve? Did they, too, feel the weight of the unknown?

With each face I sculpted—whether of the living person before me or an ancestor known only through fossilized remains—I was ultimately asking the same question: What does it mean to be alive knowing we will die? In the absence of supernatural promises, how do we face the brevity of our existence? These questions became the current underlying all my work. In that creative space, I could trace the lineage of human awareness from its earliest glimmers to its present complexity. I hoped that by looking backward—deeply and carefully—I might illuminate the present. That by understanding our origins, I might better comprehend how to live with the knowledge of my own inevitable ending.

With this approach, the tempest of existential anxiety began to lose its fury. The waves calmed. My ship found equilibrium—for a time.